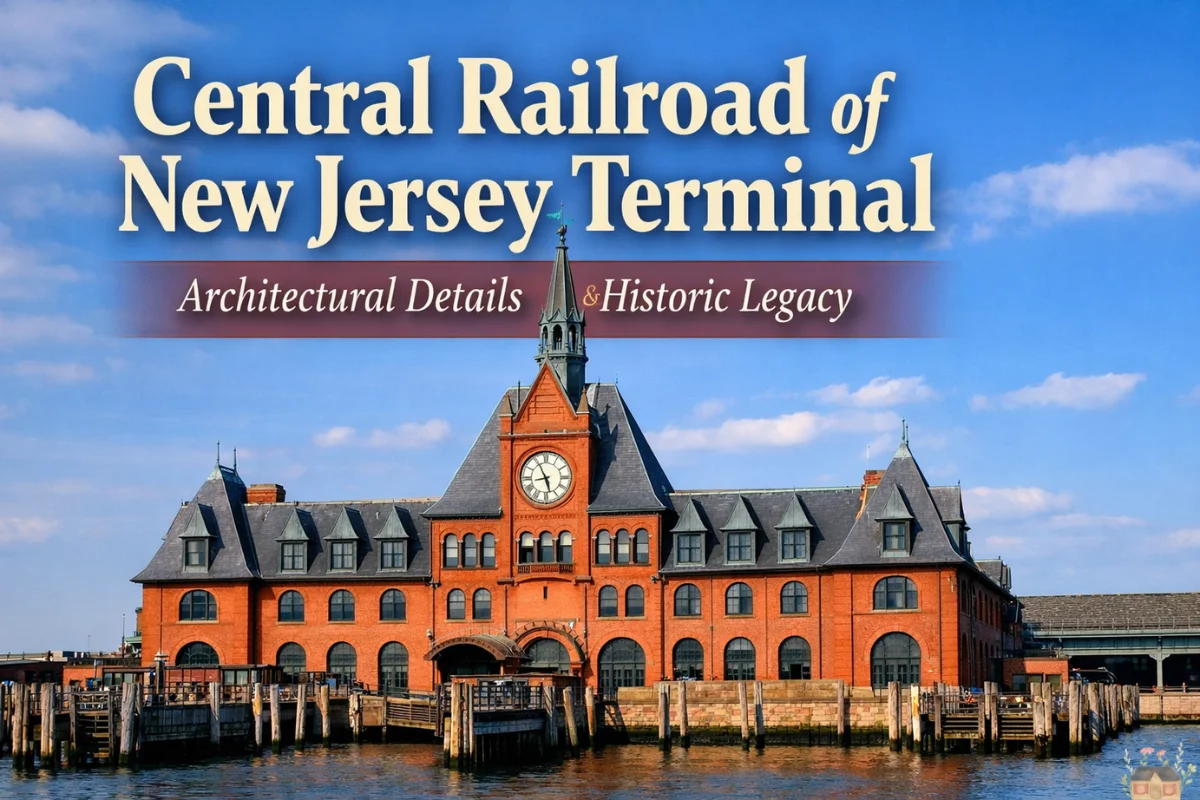

Standing at the northern edge of Liberty State Park, the Central Railroad of New Jersey (CRRNJ) Terminal—often called the Communipaw Terminal—is more than a relic of the golden age of rail. It is an architectural bridge between the industrial expansion of the 19th century and the modern preservation movement. For millions of immigrants traveling from Ellis Island, this building was the first “mainland” structure they ever touched, making its design a symbolic introduction to the American aesthetic.

Understanding the central railroad of New Jersey terminal architectural details requires looking beyond the red brick facade. The terminal is a masterclass in the Richardsonian Romanesque style, a design language that favored heavy masonry, dramatic arches, and a sense of permanence that mirrored the growing power of the American railroad industry.

The Vision of Peabody & Stearns

Completed in 1889, the current terminal was designed by the prestigious Boston-based firm Peabody & Stearns. At the time, the firm was known for high-end residential and civic projects, and they brought a sense of “Gilded Age” elegance to what was essentially a massive transfer station.

The architects were confronted with a significant functional challenge: the terminal had to serve as a high-volume intermodal hub, connecting deep-water ferry slips with a massive rail network. The result was a “T-shaped” floor plan. The head of the T faced the Hudson River to accommodate the ferry docks, while the tail housed the grand waiting room and ticketing concourse, extending westward toward the tracks.

Richardsonian Romanesque Influence

The terminal is one of the premier examples of the Richardsonian Romanesque style in the New York Harbor area. This style is characterized by:

-

Massive Masonry: The use of heavy red brick and contrasting brownstone trim creates a feeling of “gravity” and stability.

-

Rounded Arches: Unlike the pointed arches of Gothic architecture, the CRRNJ terminal uses wide, semi-circular arches for its windows and doorways, a hallmark of the Romanesque tradition.

-

Cylindrical Towers: The structure features a prominent clock tower and a cupola that served as both a functional timepiece for travelers and a navigational landmark for ships in the harbor.

Exterior Architectural Features

The exterior of the CRRNJ Terminal was built to withstand the harsh, salty environment of the Jersey City waterfront. The materials chosen were not just for show; they were selected for their durability against the vibrations of heavy locomotives and the corrosive effects of the river air.

The Clock Tower and Cupola

The most recognizable feature of the terminal is its central clock tower. Topped with a copper-clad cupola, the tower reaches high above the waterfront, once visible to captains navigating the Hudson. Recent restoration efforts have focused on the cupola’s structural integrity, using modern laser scanning to document the plumb measurements of the original framing.

Masonry and Ornamentation

The primary material is a deep red Philadelphia pressed brick, accented by Belleville brownstone. The windows are framed by heavy stone lintels, and the gables feature intricate brickwork patterns.

-

Dormers: The third floor features a series of steep-pitched dormers that break up the roofline, adding verticality to the otherwise horizontal mass of the building.

-

Finials and Rooftop Caps: The roof system is adorned with decorative copper finials, which have been painstakingly restored to their 1889 appearance to prevent water infiltration and maintain historical accuracy.

Interior Details: The Grand Waiting Room

The heart of the terminal is the Grand Waiting Room, a cavernous space designed to handle 30,000 to 50,000 passengers daily during its peak years. The architectural details here were meant to inspire awe in arriving immigrants and comfort for daily commuters.

Iron Trusses and Natural Light

One of the most significant engineering feats of the interior is the use of exposed iron trusses. These trusses allow for a massive, open-span ceiling without the need for intrusive support columns in the center of the room. This design ensured that large crowds could move efficiently between the ticketing windows and the platforms.

-

Skylights: To reduce the need for artificial lighting, the architects incorporated a series of large skylights into the roof. This flooded the concourse with natural light, highlighting the intricate textures of the walls and flooring.

-

English Glazed Tiles: The lower portions of the interior walls were lined with English glazed tiles. These were chosen for their aesthetic appeal and because they were easy to clean—a necessity in a building filled with coal soot and steam.

The Concourse and Ticketing Areas

The transition between the waiting room and the train platforms is marked by a wide concourse. Originally, this area featured ornate wooden ticketing booths and brass fixtures. While much of the original furniture was lost during the decades of abandonment (1967–1975), restoration teams have successfully recreated the “spirit” of the space using historical photographs and surviving architectural fragments.

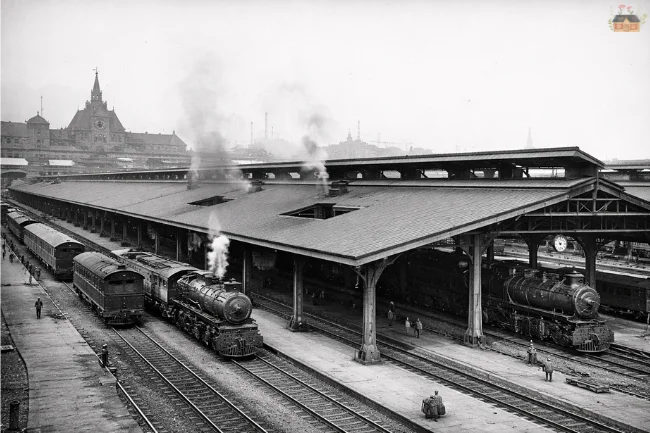

The Bush Train Sheds: An Engineering Marvel

While the terminal building itself was finished in 1889, the Bush-type train sheds were added between 1912 and 1914. Designed by engineer Abraham Lincoln Bush, these sheds represent a turning point in railroad engineering.

Before the Bush shed, most stations used large, high-arched “balloon” sheds. However, these trapped smoke and steam, making the platforms dark and hazardous. The Bush design utilized a lower profile with specialized “smoke slots” directly over the locomotive tracks.

Structural Composition of the Sheds

The sheds at the CRRNJ terminal were once the largest of their kind ever built, covering approximately 7.5 acres and 20 tracks.

-

Materials: The structure consists of cast iron columns, steel framing, and reinforced concrete canopy roofs.

-

Ventilation: The slots allowed locomotive exhaust to vent directly into the atmosphere, keeping the passenger platforms clear of smoke.

-

Endangered Status: Unlike the main terminal building, the train sheds have not been fully restored. They currently stand in a state of “arrested decay,” protected by the state but awaiting the massive funding required to stabilize the concrete and steel.

Architectural Comparison: CRRNJ vs. Hoboken Terminal

The CRRNJ terminal was one of five major passenger hubs on the Hudson waterfront. Today, only the CRRNJ and the Lackawanna (Hoboken) Terminal remain.

| Feature | CRRNJ Terminal (Jersey City) | Hoboken Terminal (Lackawanna) |

|---|---|---|

| Architectural Style | Richardsonian Romanesque | Beaux-Arts / Renaissance Revival |

| Primary Material | Red Brick & Brownstone | Copper-clad Steel & Limestone |

| Train Shed Type | Bush Shed (Largest ever built) | Bush Shed |

| Waterfront Presence | Clock Tower with Cupola | Large “Lackawanna” Neon Sign |

| Current Use | Museum / Ferry Gateway | Active Transit Hub (NJ Transit) |

Restoration and Preservation Efforts

The terminal’s survival is a miracle of historic preservation. After the Central Railroad of New Jersey declared bankruptcy in 1967, the building was abandoned and fell into disrepair. It was eventually incorporated into Liberty State Park in 1975.

Modern Challenges

Restoring a waterfront building of this scale involves unique technical hurdles:

-

Mortar Analysis: During the recent “Brick Repointing” project, samples of the original 1889 mortar were chemically analyzed. This ensured the new mortar matched the original’s flexibility and breathability, preventing the bricks from cracking.

-

3D Laser Scanning: Engineers now use 3D scanning to monitor the movement of the ferry slips and the terminal’s foundation, which sits on reclaimed land and ballast from 19th-century ocean vessels.

-

Climate Resilience: Following Superstorm Sandy in 2012, the terminal underwent extensive electrical and structural upgrades to protect its historic interior from future flooding.

Exploring the Terminal Today

Visitors to Liberty State Park can explore the terminal free of charge. While the trains no longer run, the building serves as the departure point for ferries to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island.

Walking through the terminal, you can still see the original ironwork and the vast “gateway” arches that once welcomed the world. The interpretive displays inside provide a deeper look into the lives of the workers and travelers who once filled this space.

Key Highlights for Architecture Enthusiasts

-

The West Gable Wall: Recently repointed, this wall offers the best view of the original Philadelphia brickwork.

-

The Ferry Slips: Although the wooden housing for the slips is gone, the restored ferry concourse provides a clear view of how passengers transitioned from rail to water.

-

The Iron Trusses: Look up in the grand waiting room to see the structural “skeleton” that has supported the roof for over 135 years.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What style of architecture is the Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal?

The terminal is primarily designed in the Richardsonian Romanesque style. This is evidenced by its heavy masonry, rounded arches, and prominent towers, which were characteristic of the late 19th-century preference for buildings that felt permanent and monumental.

2. Who was the architect of the CRRNJ Terminal?

The main terminal building was designed by the Boston architectural firm Peabody & Stearns. The massive train sheds, added later in 1914, were designed by engineer Abraham Lincoln Bush.

3. Why is the train shed significant?

The Bush-type train shed at the terminal was the largest ever constructed, covering 20 tracks and over 7 acres. Its innovative design allowed for better ventilation of locomotive smoke, a major improvement over the earlier “balloon” style sheds.

4. What materials were used in the terminal’s construction?

The exterior is composed of red brick and brownstone, while the interior features iron trusses, English glazed tiles, and large glass skylights. The roof and cupola are adorned with copper detailing.

5. Is the Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal still in use?

While it no longer functions as a railroad terminal, it is an active historic site and transportation hub for ferries. It serves as the main ticketing and departure point for visitors traveling to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island.

The Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal remains a vital piece of the American architectural landscape. Its blend of Richardsonian Romanesque grandeur and industrial engineering reflects a time when public infrastructure was built to be both beautiful and enduring. Whether you are interested in the technical details of 19th-century masonry or the social history of the millions who passed through its doors, the terminal stands as a testament to the power of preservation.

Learn about Architecture et du Patrimoine Berlin Wall

For broader information, visit Wellbeing Makeover

I’m Salman Khayam, the founder and editor of this blog, with 10 years of professional experience in Architecture, Interior Design, Home Improvement, and Real Estate. I provide expert advice and practical tips on a wide range of topics, including Solar Panel installation, Garage Solutions, Moving tips, as well as Cleaning and Pest Control, helping you create functional, stylish, and sustainable spaces that enhance your daily life.