The Berlin Wall was never a static object. To understand the architecture et du patrimoine Berlin Wall (architecture and heritage of the Berlin Wall), one must view it as a biological entity that evolved through four distinct generations of design. What began as a crude barbed-wire fence in 1961 eventually transformed into a sophisticated, multi-layered “death strip” by the 1980s. Today, its heritage is not defined by its ability to divide, but by how its remnants have been repurposed into a landscape of remembrance, art, and urban integration.

Berlin’s architectural identity is permanently scarred—and paradoxically enriched—by the void the Wall left behind. Mapping this heritage requires an analysis of the physical structures themselves and the “no-man’s land” that dictated the city’s development for nearly three decades.

The Four Generations of Wall Construction

The architectural history of the Wall is a study in escalating security and industrial design. It was not built overnight in its final form; rather, it was a work in progress, constantly refined by East German engineers to eliminate “weak points.”

First Generation: The Provisional Barrier (1961)

In the early hours of August 13, 1961, the border was closed with barbed wire and torn-up pavement. This was a tactical, rapid-response architecture intended to stop the immediate flow of refugees. Within days, workers began replacing wire with hollow blocks and concrete slabs.

Second Generation: The Improved Wall (1962–1965)

The second iteration saw the introduction of a more permanent structure. The wall was reinforced, and the concept of the “hinterland” wall—a second barrier further inside East Berlin—began to take shape. This created a controlled zone between the two walls.

Third Generation: The Grenzmauer 68 (1965–1975)

This version utilized concrete slabs supported by steel girders and concrete posts. It looked more like a permanent industrial installation. It was during this phase that the “death strip” became a standardized architectural feature, complete with watchtowers and signal wires.

Fourth Generation: Stützwandelement UL 12.11 (1975–1989)

The most iconic version of the Wall, the one largely seen in photographs of 1989, was known as the Grenzmauer 75. These were L-shaped reinforced concrete segments, each nearly 12 feet high. They were designed to be mass-produced, easily transported, and resistant to being rammed by vehicles. The rounded pipe on top was a deliberate architectural choice to make it nearly impossible for a climber to get a grip.

The Anatomy of the Death Strip

The architecture et du patrimoine Berlin Wall is often misunderstood as a single line. In reality, it was a complex system. The “Wall” was actually a sophisticated border installation that occupied a significant amount of urban space.

| Component | Architectural Purpose | Material/Design |

|---|---|---|

| The Outer Wall | Physical barrier facing West Berlin | Reinforced concrete UL 12.11 segments |

| The Signal Fence | Triggered alarms in watchtowers | Expanded metal with electric sensors |

| Anti-Vehicle Trenches | Prevented heavy vehicle breakthroughs | Deep excavated ditches |

| The Kolonnenweg | Patrol road for border vehicles | Concrete perforated plates |

| Light Corridors | High-intensity night surveillance | Modernist industrial floodlights |

| Watchtowers | Elevated observation points | BT-9 and BT-11 concrete designs |

Patrimoine and the Post-1989 Urban Vacuum

When the Wall fell, the primary instinct of Berliners was to erase it. The physical barrier was a symbol of trauma, and its rapid demolition was a form of collective therapy. However, this created a unique architectural challenge: a 155-kilometer-long “scar” running through the heart of a major metropolis.

The heritage (patrimoine) of the Wall is now preserved in three distinct ways: physical remnants, memorial landscapes, and “ghost” traces in the pavement.

The East Side Gallery: Art as Preservation

Perhaps the most famous piece of the Wall’s architectural heritage is the East Side Gallery. This 1.3-kilometer section of the “hinterland” wall was painted by artists from all over the world in 1990. Here, the architecture serves as a canvas. The heritage value shifted from military security to a monument for freedom. Maintaining this section is a constant struggle between preserving the original 1990 paint and protecting the concrete from the elements.

The Bernauer Straße Memorial

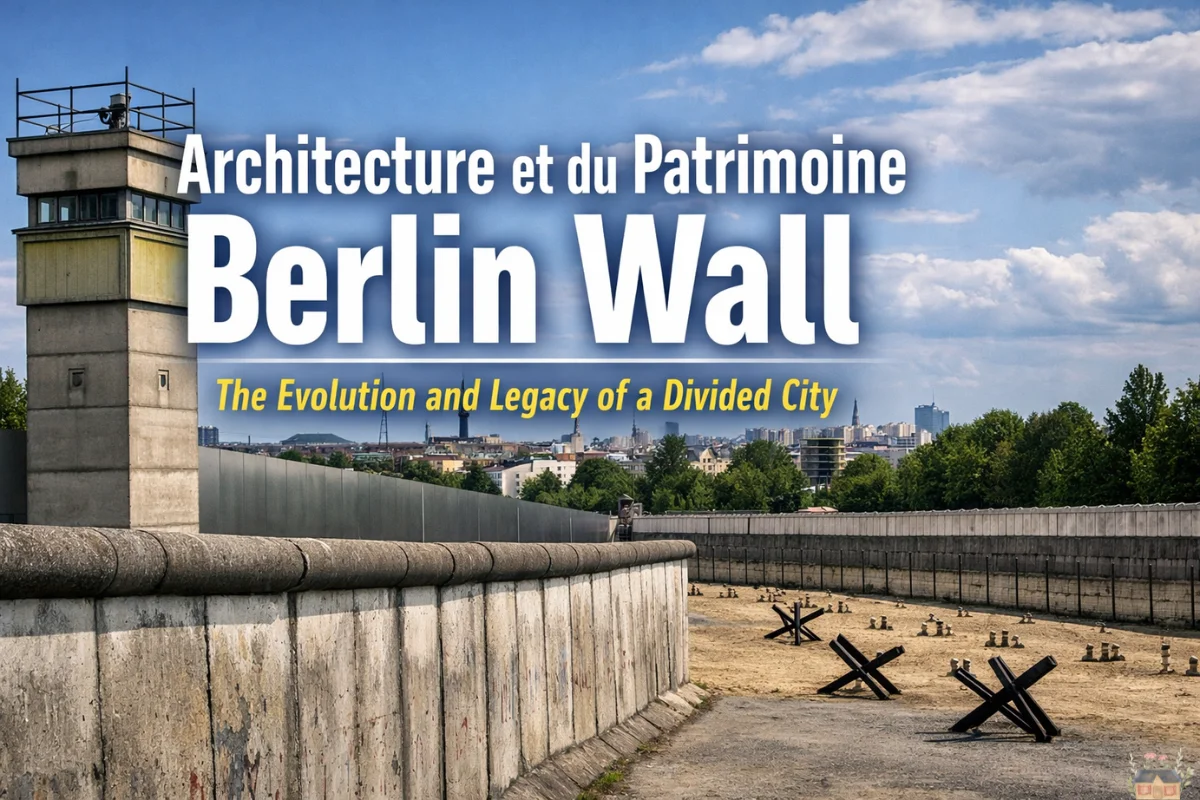

For those seeking a more clinical and historical understanding of the architecture et du patrimoine Berlin Wall, Bernauer Straße offers the most authentic preservation. It is the only place where a full section of the border complex, including the watchtower and the “no-man’s land,” has been kept intact. The architecture here is somber, utilizing rusted steel rods to mark where the wall once stood, allowing visitors to visualize the barrier without physically blocking the urban flow.

The Watchtowers: Brutalist Sentinels

At the height of the border’s operation, there were over 300 watchtowers. Only a limited number can still be seen. These towers represent a specific niche of Cold War Brutalist architecture.

The BT-11 watchtower, with its panoramic observation windows and square profile, is the most recognizable. These were not built for comfort; they were functional, modular units designed for maximum visibility. The preservation of these towers, such as the one near Potsdamer Platz, serves as a vertical reminder of the surveillance state. They are architectural “punctuation marks” in a city that has otherwise moved toward glass and transparency.

Challenges in Heritage Management

Preserving the Berlin Wall is an exercise in paradox. Concrete, especially the porous industrial grade used by the GDR, is not a durable material. It suffers from “concrete cancer” (carbonization), where the internal steel reinforcement rusts and expands, cracking the structure from the inside out.

Furthermore, the heritage of the Wall is often at odds with urban development. Because the Wall once stood on prime real estate in the city center, there is immense pressure to build over these sites. The “patrimoine” must constantly be balanced against the needs of a growing, modern city.

-

Authenticity vs. Reconstruction: Should crumbling sections be patched with modern concrete, or should they be allowed to age naturally?

-

Contextualization: A lone slab of concrete in a park means little without the surrounding “death strip” context. Heritage sites now use multimedia and landscape architecture to re-create the sense of scale.

The Ghostly Trace: The Double Row of Cobblestones

For much of Berlin, the Wall is no longer a vertical presence. Instead, it is a horizontal one. A double row of cobblestones marks the path where the Wall once stood, snaking through intersections, under buildings, and across sidewalks. This is a subtle but profound piece of urban heritage. It ensures that even in the absence of the physical architecture, the historical footprint remains part of the daily commute.

Architectural Integration in Modern Berlin

The void left by the Wall has allowed for some of the most significant architectural projects of the 21st century. Potsdamer Platz, once a desolate wasteland divided by the Wall, is now a hub of high-tech architecture. The “Band des Bundes” (Federal Ribbon), a row of government buildings across the Spree river, was designed to symbolically link East and West, literally bridging the gap where the Wall once stood.

In these cases, the absence of the Wall dictated the architecture of the new German capital. The heritage is found in the way the city has healed its wounds while refusing to hide the scars.

FAQs

1- What is the most famous architectural section of the Berlin Wall still standing?

The East Side Gallery is the most famous standing section. It is a 1.3 km stretch of the inner wall located in Friedrichshain. While it is not the “outer” wall that faced the West, its length and the iconic murals make it a primary site for understanding the Wall’s physical scale.

2- How did the architecture of the Wall change over time?

The Wall evolved from simple barbed wire (1961) to hollow blocks, then to large concrete slabs, and finally to the “Border Wall 75” (1975). This final version consisted of L-shaped reinforced concrete segments that were more durable and easier to assemble than previous versions.

3- Why are some parts of the Wall preserved while others were destroyed?

In the immediate aftermath of 1989, most of the Wall was destroyed to reunite the city and remove a symbol of oppression. Preservation efforts began later as historians argued that the physical remnants were necessary to educate future generations about the Cold War and the division of Germany.

4- Where can I see a full “Death Strip” today?

The Berlin Wall Memorial at Bernauer Straße is the only place where the entire border fortification system has been preserved. This includes the outer wall, the patrol path, the lights, and the inner wall, providing a complete view of the “architecture of division.”

5- Is the “Berlin Wall Trail” an architectural site?

The Berliner Mauerweg (Berlin Wall Trail) is a 160 km cycling and walking path that follows the former border. While it is a recreational path, it functions as a heritage site by passing through various architectural remnants, including watchtowers, former command posts, and preserved wall segments.

Conclusion

The architecture et du patrimoine Berlin Wall serves as a vital case study in how a city manages the remnants of a difficult past. From the industrial efficiency of the Grenzmauer 75 to the vibrant, lived-in heritage of the East Side Gallery, the Wall remains an inescapable part of Berlin’s DNA. It is a reminder that architecture is never neutral; it can be a tool of imprisonment or a monument to resilience.

Today, the heritage of the Wall is not found in the concrete alone, but in the spaces between—the parks, the museums, and the cobblestone lines that remind us of where the world was once split in two. As Berlin continues to grow, the challenge will remain: how to build a future that respects the physical memory of its most famous barrier.

Learn about How Architecture Has Changed Over Time Kdainteriorment

For broader information, visit Wellbeing Makeover

I’m Salman Khayam, the founder and editor of this blog, with 10 years of professional experience in Architecture, Interior Design, Home Improvement, and Real Estate. I provide expert advice and practical tips on a wide range of topics, including Solar Panel installation, Garage Solutions, Moving tips, as well as Cleaning and Pest Control, helping you create functional, stylish, and sustainable spaces that enhance your daily life.