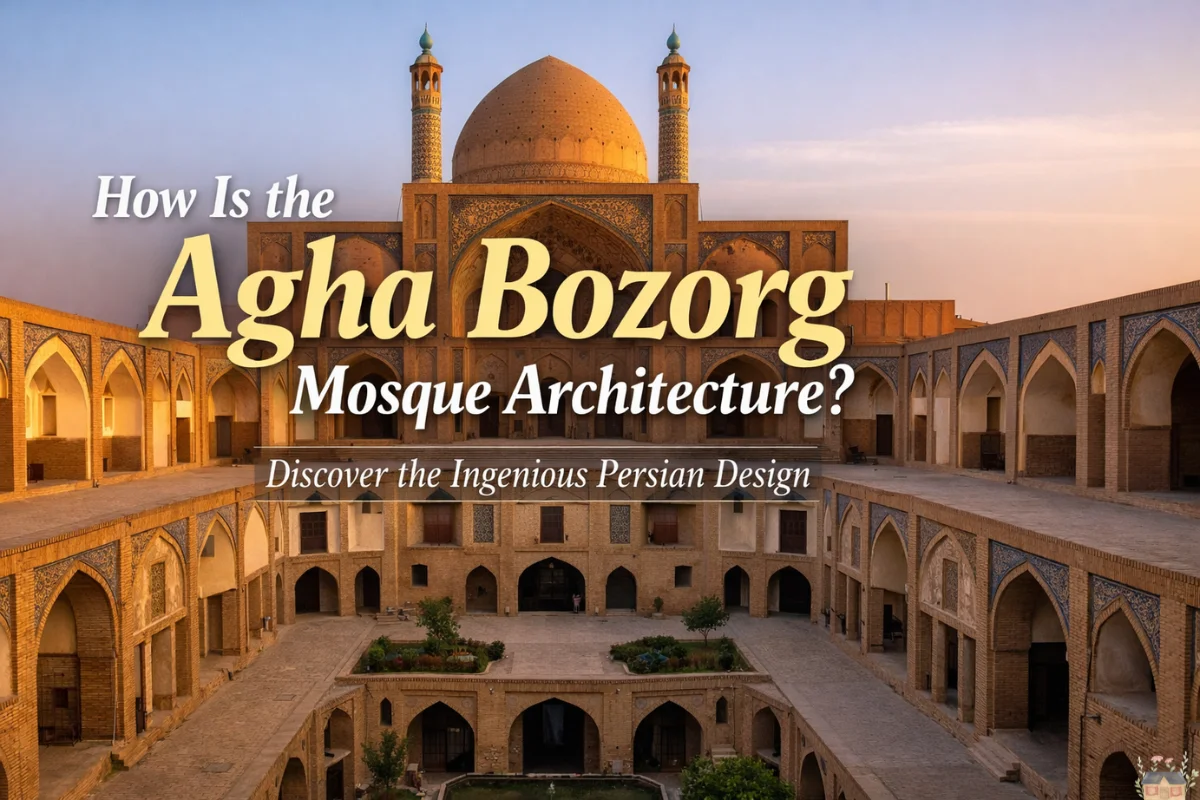

Located in the heart of Kashan, Iran, the Agha Bozorg Mosque and Madrasa stands as a testament to the ingenuity of 18th and 19th-century Persian architects. Built during the Qajar era, this structure is far more than a religious site; it is a sophisticated response to the harsh, arid climate of the Iranian central plateau. When exploring how is the Agha Bozorg mosque architecture categorized, one must look beyond simple aesthetics and examine the profound integration of functionality, symmetry, and environmental adaptation.

Historical Context and Construction

To understand the architectural significance of this site, one must first look at the period of its creation. Constructed in the late 18th century, with finishing touches applied during the reign of Mohammad Shah Qajar, the mosque was built for Mulla Muhammad Mahdi Naraqi, a prominent cleric known as Agha Bozorg.

Kashan was a city recovering from a devastating earthquake in 1778. The reconstruction period allowed for a refined architectural style that blended Safavid traditions with the emerging Qajar aesthetic. The result was a structure that prioritized spatial economy and cooling mechanisms, essential for a city where summer temperatures often exceed 40°C.

The Sunken Courtyard: A Masterstroke of Climate Control

One of the most striking features when analyzing how is the Agha Bozorg mosque architecture is the use of a “Gowdar-Zal” or sunken courtyard. Unlike many traditional mosques, where the central courtyard sits at street level, Agha Bozorg features a multi-level design.

The lower level serves as a madrasa (theological school), while the upper level provides access to the mosque’s prayer halls. This sunken design serves two primary purposes:

-

Natural Insulation: By placing the student quarters and the primary courtyard below ground level, the structure utilizes the earth’s thermal mass. This keeps the lower rooms significantly cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter.

-

Access to Water: The lower level was historically connected to the city’s qanat system (underground aqueducts), allowing fresh water to flow through the courtyard, providing both humidity and a soothing psychological effect.

Symmetry and the Four-Iwan Layout

The mosque follows the classic Persian “Four-Iwan” layout, but with a unique twist. Typically, an Iwan is a rectangular hall or space, usually vaulted, walled on three sides, with one end entirely open. In Agha Bozorg, the symmetry is meticulously maintained to create a sense of infinite balance.

The main dome sits atop a massive structure supported by heavy brick pillars. What makes this mosque unique is that the prayer hall is open on three sides. This is a radical departure from the enclosed, heavy-set domes of the Safavid era. By opening the sides, the architect, Haj Sa’ban-ali, ensured that air could circulate freely through the prayer hall, cooled by the shade of the Iwans and the moisture of the sunken courtyard.

Key Architectural Specifications

The Interplay of Light and Shadow

In desert architecture, light is both a blessing and a challenge. The architects of Agha Bozorg used light as a building material in its own right. The intricate brickwork patterns (khataei) create a shifting tapestry of shadows throughout the day.

The use of “Karbandi” (intersecting arches) in the ceilings serves a dual purpose. Structurally, it distributes the weight of the roof. Artistically, it creates complex geometric shapes that catch the low-slung sun, illuminating the interior without the need for large, heat-leaking windows. The mihrab, or prayer niche, is decorated with delicate tilework and inscriptions, serving as the focal point of the spiritual space while remaining integrated into the overall brick aesthetic.

Read Also: Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal Architectural Details: A Complete Guide to Design & History

Minimalism in the Qajar Era

While many mosques from the Safavid period are known for their vibrant blue tiles and gold leaf, Agha Bozorg is celebrated for its restraint. The architecture relies heavily on the natural color of the bricks. This “mud-brick” aesthetic is not a sign of poverty but a deliberate choice to harmonize with the surrounding desert landscape.

The ornamentation is concentrated in specific areas:

-

The Entrance Portal: Featuring intricate stalactite vaulting (muqarnas).

-

The Dome: A masterclass in brick patterns that create visual movement.

-

The Wooden Doors: Often carved with geometric patterns that mirror the brickwork of the walls.

This minimalist approach highlights the “geometry of the void.” In this mosque, what is not built is as important as what is built. The large open spaces, the height of the Iwans, and the depth of the courtyard all work together to create a sense of monumental scale without feeling overwhelming.

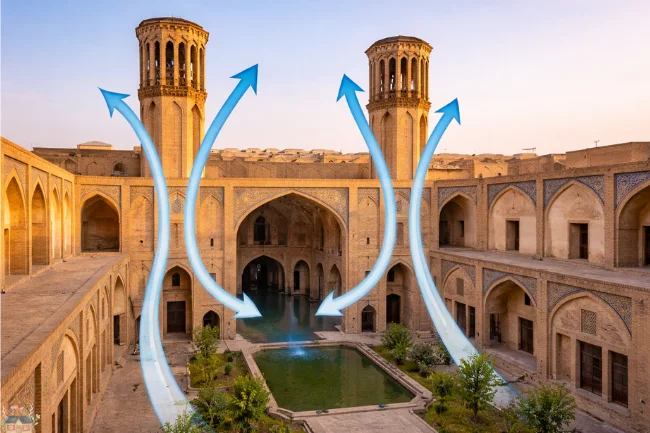

Passive Cooling and the Wind Towers

No discussion on how is the Agha Bozorg mosque architecture functions would be complete without mentioning the badgirs, or wind catchers. These tall, chimney-like structures are positioned to catch the slightest breeze.

The wind towers at Agha Bozorg are integrated into the walls of the mosque. They funnel air down into the lower levels and across the surface of the water in the courtyard pools. As the water evaporates, it absorbs heat, effectively acting as a natural air conditioning system. This demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of fluid dynamics and thermodynamics long before the advent of modern engineering.

The Madrasa: A Space for Contemplation

The integration of the school within the mosque complex speaks to the Islamic tradition of combining faith and reason. The student cells (rooms) line the sunken courtyard. Each cell is designed for privacy and study, featuring small windows that look out onto the central garden.

This layout fostered a community environment. Students were physically situated below the prayer halls, metaphorically and literally supported by the foundation of the mosque. The proximity to the mosque’s dome provided a sense of spiritual oversight, while the seclusion of the sunken courtyard provided the quiet needed for rigorous academic pursuit.

Read Also: Architecture et du Patrimoine Berlin Wall: Design & Legacy

Sustainability and Local Materials

The Agha Bozorg mosque is a prime example of sustainable architecture. Because it was built primarily from local clay and straw, the building has a very low carbon footprint by modern standards. Brick is an ideal material for the desert because it has high thermal inertia; it absorbs heat during the day and releases it slowly at night, keeping the interior temperatures stable.

Furthermore, the maintenance of such a structure relies on traditional masonry techniques that have been passed down through generations in Kashan. This ensures that the building remains a living part of the community’s heritage rather than a static monument.

Preservation and Modern Significance

Today, the Agha Bozorg mosque remains an active place of worship and a major draw for students of architecture. It serves as a reminder that “smart” architecture does not always require high-tech solutions. By observing the movements of the sun, the direction of the wind, and the properties of the earth, the architects created a building that has remained functional and beautiful for over two centuries.

The site is frequently studied by those interested in “bioclimatic” design—architecture that works with the local climate to provide comfort. In an era of rising global temperatures and energy crises, the lessons found in the brickwork of Agha Bozorg are more relevant than ever.

Frequently Asked Questions

Summarizing the Architectural Legacy

The Agha Bozorg mosque is a masterpiece of equilibrium. It balances the spiritual with the educational, the monumental with the minimalist, and the blistering heat of the desert with the cool shadows of its sunken gardens. Its architecture is not merely about decoration; it is about survival and serenity in a challenging environment.

By studying the way the dome breathes and the courtyard cools, we gain insight into a culture that viewed building not as a conquest of nature, but as a conversation with it. Whether you are an architect, a historian, or a traveler, the Agha Bozorg mosque offers a profound lesson in how humanity can create lasting beauty through a deep understanding of the natural world.

Learn about the Mission Revival Architecture Time Period

For broader information, visit Wellbeing Makeover

I’m Salman Khayam, the founder and editor of this blog, with 10 years of professional experience in Architecture, Interior Design, Home Improvement, and Real Estate. I provide expert advice and practical tips on a wide range of topics, including Solar Panel installation, Garage Solutions, Moving tips, as well as Cleaning and Pest Control, helping you create functional, stylish, and sustainable spaces that enhance your daily life.